A palace of pageantry and quiet craftsmanship

Balconies of celebration, gilded rooms, gardens of calm, carriages and uniforms—tradition meeting a city that never stops.

Table of Contents

Origins and transformations

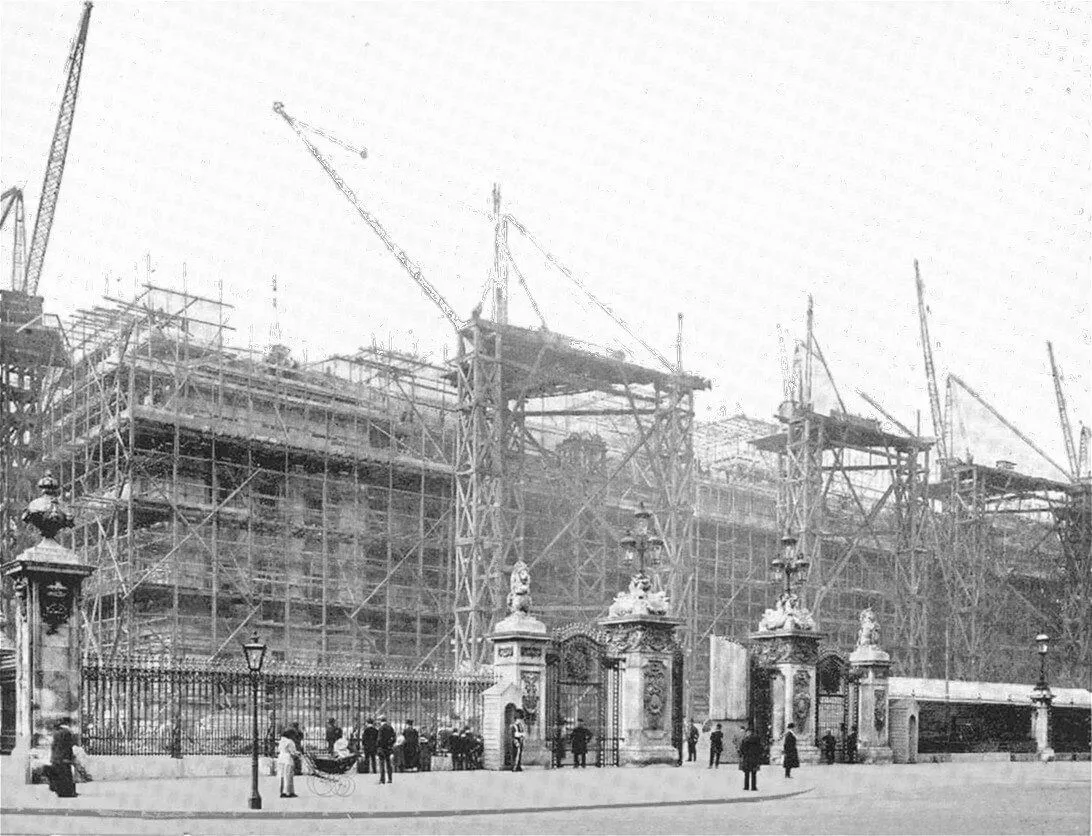

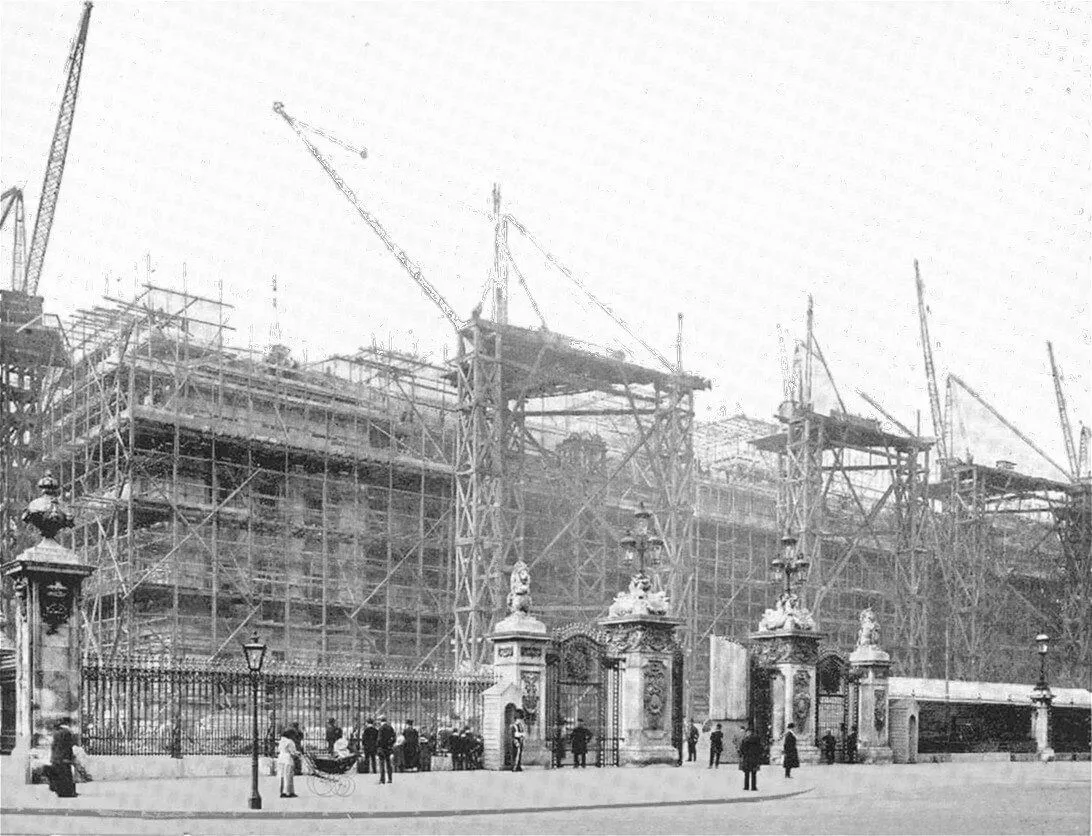

Buckingham Palace began modestly as Buckingham House in the early 18th century—a grand townhouse on the edge of St James’s Park. Over decades, it became a theatre of monarchy: remodelled and expanded, faced with Portland stone, and shaped by architects like John Nash and Edward Blore who threaded ceremony into corridors and courtyards.

What we see today is the layered result of tastes, needs, and public life. Wings added for function and procession, rooms adorned for receptions and investitures, and a forecourt designed for pageantry. It is a working palace where architecture is not just backdrop but instrument—a place tuned for moments that matter.

Public life and ceremony

Buckingham is where ceremony becomes a shared language: the Changing of the Guard with crisp drill and brass music, investitures that celebrate service, and balcony appearances when national feeling needs a focal point. The palace is both stage and sanctuary—public ritual outside, private preparation within.

These rhythms bind the city to the Crown: soldiers move with practiced grace, carriages roll from the Mews, and crowds gather under the Victoria Memorial. Even when you visit quietly, you feel those traces—the geometry of gates, the sweep of the Mall, and the sense that London itself pauses to listen.

Architecture and interiors

Inside, gilding does more than glitter—it frames stories. Silk‑covered walls, parquet floors, chandeliers that catch London’s pale light, and portraits that watch kindly from their gilded frames. Each State Room balances spectacle with hospitality: spaces set for receptions, investitures, and state occasions where protocol is poetry and craftsmanship is the chorus.

Architecture here is choreography: routes for guests, sightlines for procession, and a cadence that guides you from room to room. The result is immersive without hurry, inviting you to notice details—the curve of a banister, a thread of gold in a tapestry, a painting placed so its gaze meets yours as you turn.

Royal collections and art

The Royal Collection is a constellation of art gathered over centuries—paintings, drawings, sculpture, porcelain, textiles—objects that travelled through time and taste to live here. Exhibitions in the Queen’s Gallery rotate, offering windows into different chapters and themes, while State Rooms display a selection that complements ceremony.

It is a living collection: curated for teaching, celebration, and reflection. Audio guides add voices to objects—how a brushstroke found its light, why a porcelain service matters, where a tapestry was woven. The result feels personal, especially when you linger and let a single painting draw you close.

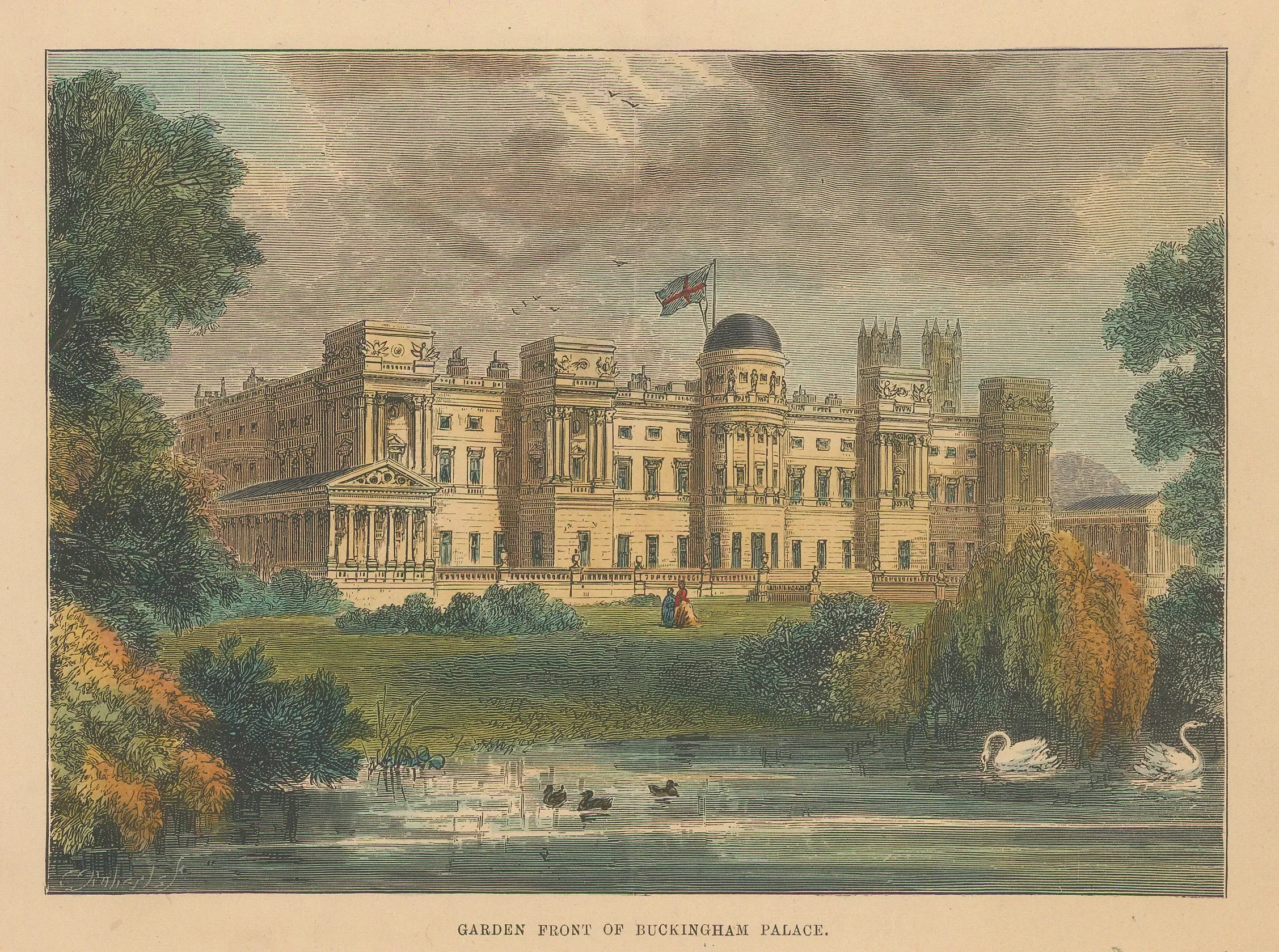

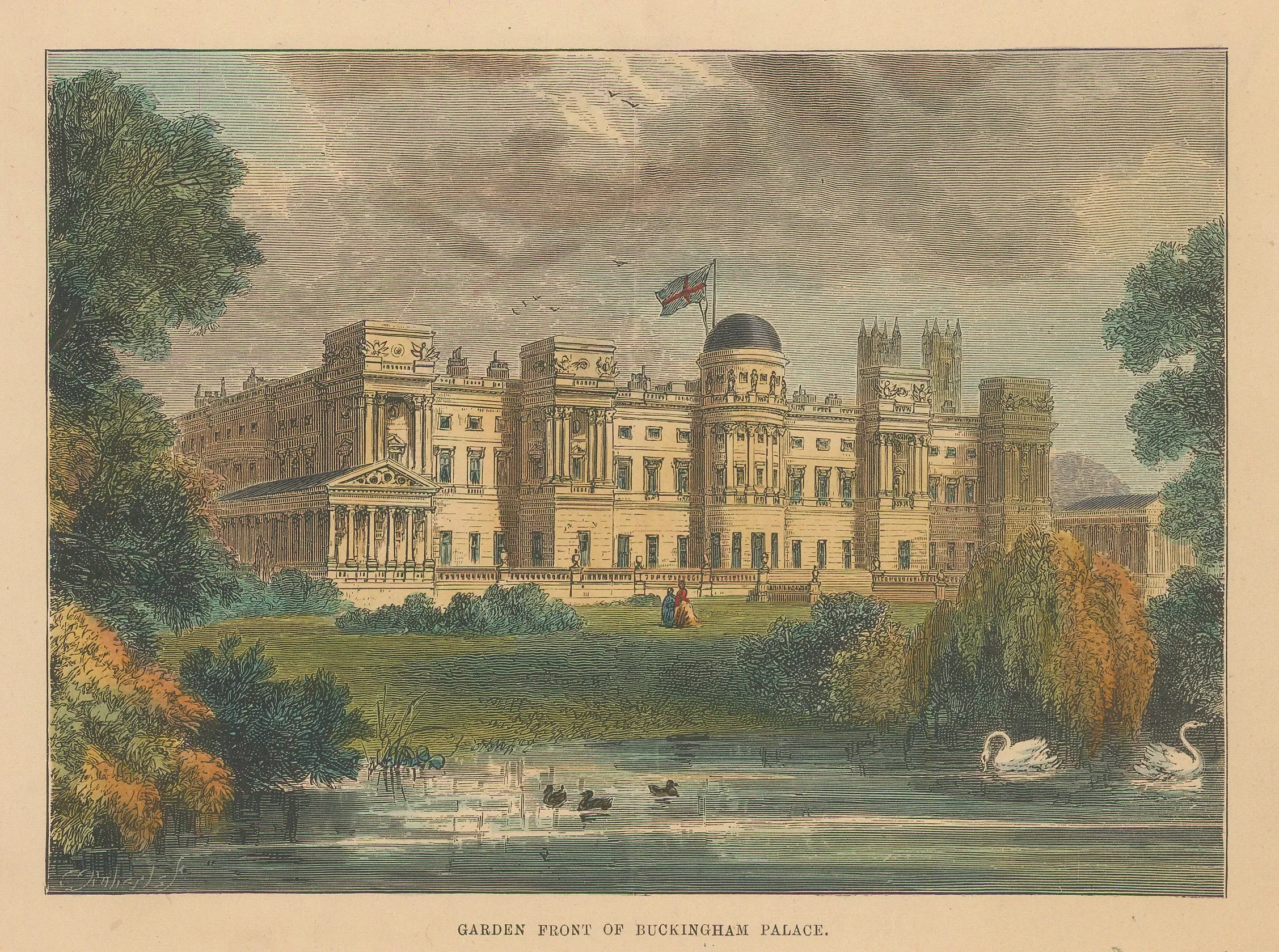

Gardens and the Mews

Behind the façade, the gardens are surprisingly gentle—lawns and lakes where city sounds hush. Paths curve with intention, lending space to exhale after the gleam of interiors. In the Royal Mews, horses and carriages bring ceremony into the everyday: harness rooms, coach houses, and the artistry of movement.

The Mews teaches that pageantry is practical craft: leatherwork, training, and care meet tradition in a well‑oiled routine. Paired with the gardens, it rounds out the visit—spectacle answered by calm, grandeur balanced by working life.

Victorian expansion and symbolism

The 19th century reshaped Buckingham into a national emblem. Under Queen Victoria, the palace became the principal royal residence, expanding to host larger courts and events. The East Front—today’s familiar face—framed the balcony that would become a shorthand for national moments.

Symbolism crystallised: the palace as a place where private decisions meet public rituals. Architecture served identity, and identity served continuity—definitions that still echo when the balcony doors open and a crowd finds itself a chorus.

War, resilience, and continuity

The palace stood through conflict. Bomb damage during the Second World War marked it physically and historically; repairs were practical and symbolic, affirming presence when absence would have been easier. Continuity mattered—ceremony persisted, and the building remained a compass in uncertain times.

Resilience here is quiet: masonry restored, routines adapted, and staff who understood that place can steady people. When you visit, you sense that steadiness in small ways—the confidence of routes, the unshowy care in how rooms are kept, the way history speaks without raising its voice.

Modernisation and accessibility

Today’s palace balances tradition with modern needs: conservation science behind gilded frames, climate control discreetly sustaining textiles and paintings, and accessibility threaded through routes so more people can feel welcomed.

Security and hospitality work hand in hand: timed entry, clear guidance, and trained staff make visiting feel gracious and simple—ceremony for everyone, not just the invited.

The balcony and national memory

The balcony is a stage, but also a ritual of recognition. Royal family members step out, the crowd looks up, and for a moment, private and public align. Announcements, jubilees, weddings—memories attach to a single architectural gesture.

That gesture turns architecture into feeling: stone and glass becoming chorus. Even if you visit when the balcony is quiet, you see the potential in the façade—the promise of shared occasions and a city that knows where to gather when it needs to celebrate or reflect.

Planning with historical context

Begin with ceremony if you can—watch the Guard, then move indoors. In the State Rooms, look for craftsmanship that rewards a slower pace: marquetry, gilding, portraits placed for conversation, and ceilings that turn light into music.

Context makes rooms richer: read labels, listen to the audio guide, and pair indoors with the Mews or Gallery so pageantry and art answer each other.

Westminster and surroundings

St James’s Park wraps the palace in green, with bridges and water that make Westminster feel softer. Walk to the Mall, glance towards Admiralty Arch, and let the sightlines explain how the city choreographs its grand gestures.

Nearby, Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster anchor faith and governance; Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery show art and public space in conversation. Buckingham sits quietly at the centre, confident and calm.

Complementary nearby sites

Royal Mews, Queen’s Gallery, Westminster Abbey, the Palace of Westminster, St James’s Palace, and the National Gallery make an elegant circuit.

Pairing sites brings contrast: ceremony and worship, art and architecture, crowds and gardens. It turns a single visit into a day that feels full yet unhurried.

Enduring legacy of Buckingham

Buckingham Palace carries stories of service, celebration, and continuity. It is where announcements find an audience, where craft supports ceremony, and where public feeling finds a place to gather.

Conservation, adaptation, and thoughtful access keep its meaning alive—tradition with room to breathe, a palace that belongs to many moments and generations.

Table of Contents

Origins and transformations

Buckingham Palace began modestly as Buckingham House in the early 18th century—a grand townhouse on the edge of St James’s Park. Over decades, it became a theatre of monarchy: remodelled and expanded, faced with Portland stone, and shaped by architects like John Nash and Edward Blore who threaded ceremony into corridors and courtyards.

What we see today is the layered result of tastes, needs, and public life. Wings added for function and procession, rooms adorned for receptions and investitures, and a forecourt designed for pageantry. It is a working palace where architecture is not just backdrop but instrument—a place tuned for moments that matter.

Public life and ceremony

Buckingham is where ceremony becomes a shared language: the Changing of the Guard with crisp drill and brass music, investitures that celebrate service, and balcony appearances when national feeling needs a focal point. The palace is both stage and sanctuary—public ritual outside, private preparation within.

These rhythms bind the city to the Crown: soldiers move with practiced grace, carriages roll from the Mews, and crowds gather under the Victoria Memorial. Even when you visit quietly, you feel those traces—the geometry of gates, the sweep of the Mall, and the sense that London itself pauses to listen.

Architecture and interiors

Inside, gilding does more than glitter—it frames stories. Silk‑covered walls, parquet floors, chandeliers that catch London’s pale light, and portraits that watch kindly from their gilded frames. Each State Room balances spectacle with hospitality: spaces set for receptions, investitures, and state occasions where protocol is poetry and craftsmanship is the chorus.

Architecture here is choreography: routes for guests, sightlines for procession, and a cadence that guides you from room to room. The result is immersive without hurry, inviting you to notice details—the curve of a banister, a thread of gold in a tapestry, a painting placed so its gaze meets yours as you turn.

Royal collections and art

The Royal Collection is a constellation of art gathered over centuries—paintings, drawings, sculpture, porcelain, textiles—objects that travelled through time and taste to live here. Exhibitions in the Queen’s Gallery rotate, offering windows into different chapters and themes, while State Rooms display a selection that complements ceremony.

It is a living collection: curated for teaching, celebration, and reflection. Audio guides add voices to objects—how a brushstroke found its light, why a porcelain service matters, where a tapestry was woven. The result feels personal, especially when you linger and let a single painting draw you close.

Gardens and the Mews

Behind the façade, the gardens are surprisingly gentle—lawns and lakes where city sounds hush. Paths curve with intention, lending space to exhale after the gleam of interiors. In the Royal Mews, horses and carriages bring ceremony into the everyday: harness rooms, coach houses, and the artistry of movement.

The Mews teaches that pageantry is practical craft: leatherwork, training, and care meet tradition in a well‑oiled routine. Paired with the gardens, it rounds out the visit—spectacle answered by calm, grandeur balanced by working life.

Victorian expansion and symbolism

The 19th century reshaped Buckingham into a national emblem. Under Queen Victoria, the palace became the principal royal residence, expanding to host larger courts and events. The East Front—today’s familiar face—framed the balcony that would become a shorthand for national moments.

Symbolism crystallised: the palace as a place where private decisions meet public rituals. Architecture served identity, and identity served continuity—definitions that still echo when the balcony doors open and a crowd finds itself a chorus.

War, resilience, and continuity

The palace stood through conflict. Bomb damage during the Second World War marked it physically and historically; repairs were practical and symbolic, affirming presence when absence would have been easier. Continuity mattered—ceremony persisted, and the building remained a compass in uncertain times.

Resilience here is quiet: masonry restored, routines adapted, and staff who understood that place can steady people. When you visit, you sense that steadiness in small ways—the confidence of routes, the unshowy care in how rooms are kept, the way history speaks without raising its voice.

Modernisation and accessibility

Today’s palace balances tradition with modern needs: conservation science behind gilded frames, climate control discreetly sustaining textiles and paintings, and accessibility threaded through routes so more people can feel welcomed.

Security and hospitality work hand in hand: timed entry, clear guidance, and trained staff make visiting feel gracious and simple—ceremony for everyone, not just the invited.

The balcony and national memory

The balcony is a stage, but also a ritual of recognition. Royal family members step out, the crowd looks up, and for a moment, private and public align. Announcements, jubilees, weddings—memories attach to a single architectural gesture.

That gesture turns architecture into feeling: stone and glass becoming chorus. Even if you visit when the balcony is quiet, you see the potential in the façade—the promise of shared occasions and a city that knows where to gather when it needs to celebrate or reflect.

Planning with historical context

Begin with ceremony if you can—watch the Guard, then move indoors. In the State Rooms, look for craftsmanship that rewards a slower pace: marquetry, gilding, portraits placed for conversation, and ceilings that turn light into music.

Context makes rooms richer: read labels, listen to the audio guide, and pair indoors with the Mews or Gallery so pageantry and art answer each other.

Westminster and surroundings

St James’s Park wraps the palace in green, with bridges and water that make Westminster feel softer. Walk to the Mall, glance towards Admiralty Arch, and let the sightlines explain how the city choreographs its grand gestures.

Nearby, Westminster Abbey and the Palace of Westminster anchor faith and governance; Trafalgar Square and the National Gallery show art and public space in conversation. Buckingham sits quietly at the centre, confident and calm.

Complementary nearby sites

Royal Mews, Queen’s Gallery, Westminster Abbey, the Palace of Westminster, St James’s Palace, and the National Gallery make an elegant circuit.

Pairing sites brings contrast: ceremony and worship, art and architecture, crowds and gardens. It turns a single visit into a day that feels full yet unhurried.

Enduring legacy of Buckingham

Buckingham Palace carries stories of service, celebration, and continuity. It is where announcements find an audience, where craft supports ceremony, and where public feeling finds a place to gather.

Conservation, adaptation, and thoughtful access keep its meaning alive—tradition with room to breathe, a palace that belongs to many moments and generations.